Having had some exposure on TV, it wasn’t long before I was invited to fly on film sets. The very first film was in George Orwell’s classic ‘1984’, where I had to fly a Bell 47G in parallel with fellow pilot John Griffiths, who had invited me along.

But of all the film engagements I’ve done, the most famous were on the set of the James Bond movies. I did three of these which were ‘GoldenEye’, ‘The World is Not Enough’ and ‘Live and Let Die’.

My involvement started when Nigel Brackley, a good friend of mine who worked at Leavesden film studios, asked me to help them out. At that time Nigel was working on the James Bond film GoldenEye and he asked me if I would make some rotor blades for a quarter scale model they were building for use in the film. The blades would be nearly 2 metres long, 18mm thick and 12cm wide – they wanted six sets of three blades. I produced these on time and must have done a good job as Nigel phoned me up to ask if I would be interested in making moulds for a 2.5 metre long Aerospatiale Squirrel. As I completed each fuselage I would transport it back to the studios where the house modellers put in the mechanics to make them flyable.

A few days later Nigel phoned and asked me if I was busy. I wasn’t so he asked me if I would like to fly the models I’d just made. I said I would love to.

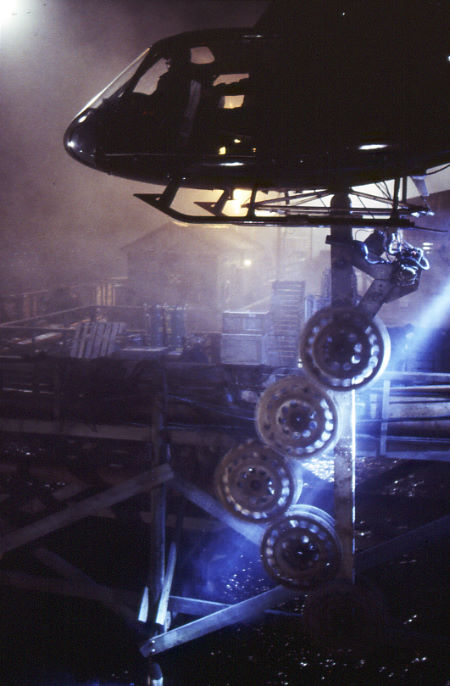

One of the more memorable scenes was in the film ‘The World is not Enough’ staring Pierce Brosnan as James Bond who is attacked by the buzz-saw-wielding helicopter at Zukovsky's Caviar Fishery. I was given the model’s transmitter, which fortunately was the same as I used with the switches in the same places. That wasn’t so bad but the real issue was that I had never flown the model before, and the flying was to take place outside amongst film equipment, props and dense scenery.

To make matters worse, the helicopter was perched on scaffolding about 2 metres off the ground, on a 1.7 metre square platform that had a slot cut out of it down the middle. Attached to the helicopter – and hanging down the slot, was a 1.7 metre chainsaw with five blades so that as the helicopter took off, the chainsaw would come up through the slot being carried by the helicopter. Because of the height of the platform I couldn’t see the top and so I would be blind when judging whether or not the chainsaw had cleared the platform. Other than these minor points it was quite straight-forward. I thought to myself - this is going to be awkward.

There would be two of us flying helicopters for this scene. The person flying the other helicopter says to me “I’ll take the right-hand side and you can take the left hand side.” For all it was worth this was a bit of relief for me as it meant I could fly a left-hand circuit which, due to the rotation of the blades, is much easier than flying a right hand circuit. My helper told me that the right hand side was much harder to fly as the set had oil rigs and various wires that would need to be avoided for anyone flying in that direction.

Following the cry of “Action!” from the producer, the other pilot took off first, which was then my cue to take off. The helicopter I was flying took off like a dream with no problems at all. But as I was flying towards the left hand side of the set, the other pilot asked me what I was doing. I said that I was positioning myself to be on the left as we had discussed, but he had now changed his mind and he wanted me to fly to the right. This meant I now had to do right-hand circuits with a 2.5 metre model I had never flown before, and I had to avoid all the objects and wires that were on that side.

The director was in radio contact with my helper so that he could pass instructions to us on where he would like us to fly. I was getting the instructions “Get lower”, so I drop 1 metre, “ Lower”, I drop another 2 metres, “Lower still”, until finally he said “That’s good - hold it there.”

I then noticed that the chainsaw I was lifting start to swing – I had hit one of the cables attached between a rig and the ground, but fortunately the wire had came out of the ground so I could carry on.

We did a couple of takes and the model I had was fantastic to fly, even with a chainsaw attached to it. We were then given the all clear to land. As I was the closest to the designated landing spot I came in first. We still had the chainsaws’ attached and so to help land there were two sets of scaffolding poles arranged as large wigwam and between these sets of poles was a net onto which the chain saw could be lowered. Once over the net a technician would call out “release” which would indicate we were in the right position and could then hit a

switch which would drop the chainsaw from the helicopter into the net. The helicopter could then be landed in the normal way. I went through the procedure with no problems and landed normally.

However, when the technician called “release” to the other flier, rather than hit the switch that would release the cable, the pilot hit the ‘engine kill’ switch instead. The helicopter sank immediately with the chain saw and ‘made love’ to one of the scaffolding poles. The resulting crash was spectacular as the model, worth around £20,000, was totally destroyed.

I had done my job and so was no longer needed as the other pilot was scheduled to fly on the other days. As I was about to leave I asked if I could stay for lunch and watch the filming that afternoon. That wasn’t a problem and so I stayed on. The other pilot was due to see the director that afternoon to discuss a number of other stunts he was due to fly, including picking up a portacabin with the helicopter . I thought – lucky bugger, I’d love to do that.

After lunch the director asked who was going to do the flying. The other pilot spoke up to which the director asked “Are you the idiot who crashed the helicopter this morning?”. When he confirmed that he was, the director said “You’re not flying - he is” and pointed to me. “Be here early in the morning” I was speechless – as was the other pilot. Before going home I was given instructions of what they wanted. On the producers pad it said ‘one helicopter, one pilot’ and in brackets ‘Len Mount’. Evidently this was very unusual as, I was told later, they don’t name the pilots. So the other pilot was now my helper – he was there to support me. I did have some fun with him by making it difficult for him to start the model. I ended up with 10 days work - the only time I have ever got work through someone else crashing.

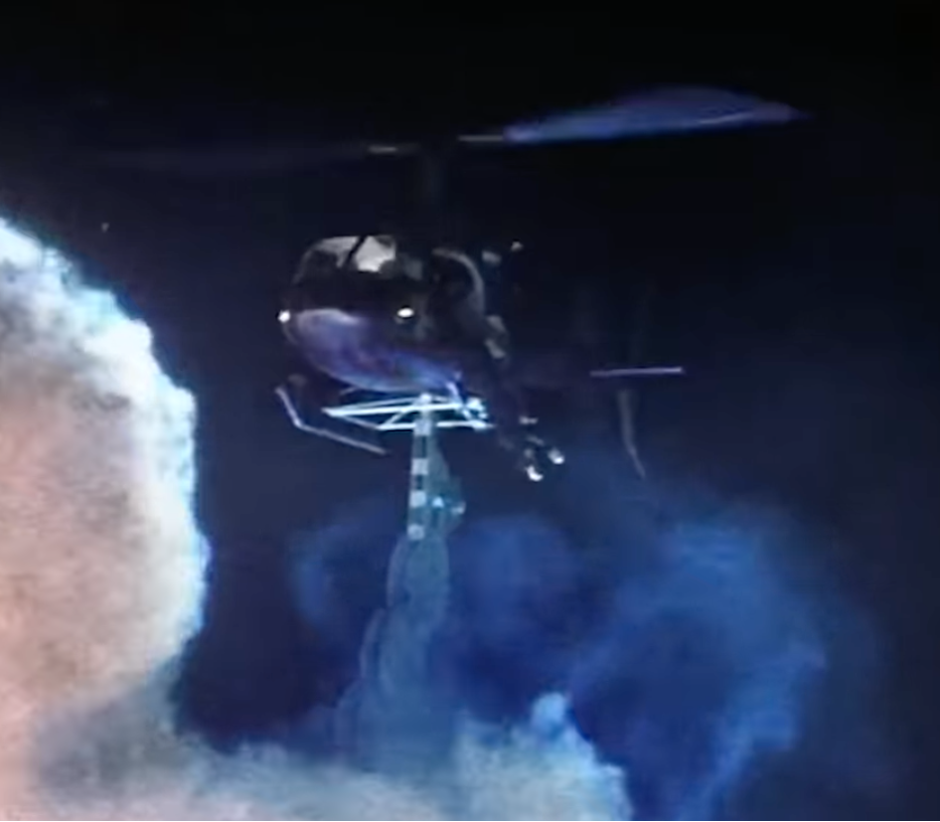

One scene that was particularly impressive was at night where the helicopters were going to get blown up. I practiced during the day with a pod and boom helicopter to get the angles and distance right. During this time we had someone take the directors place as he was on the camera checking out the film shots. The practice involved flying the helicopter over water, stopping in line with the director, turning and then flying forwards towards him.

We got it pretty good – but the real director had never practiced it. What they didn’t tell me was that the model was going to be full up of explosives – if I had known I wouldn’t have stood so close on take off. As well as the explosives the model was to take off with a chainsaw attached.

Actual filming started around midnight. I took off from a trailer – the model was on one end and I was at the other end in a 1.3 metre square hide. This was made out of 4x4 timber and 3cm thick Perspex to protect me should anything go wrong. It was also there to protect me from the explosives, although I didn’t know this at that time.

During the day flying wasn’t a problem as I could see thought the windows, however at night the window I was looking through lit up from the glare of the lights and I had trouble seeing through it. I told my helper to hang onto me as I was going to lean outside of the hide, and to pull me in as soon as he heard the explosion, so I didn’t get any shrapnel.

I took off and flew along waiting to be given the signal by the director to stop, turn 90 degrees and then fly forward. I flew along, the director called “stop”, but as anyone who flies helicopters knows, you can’t just stop as it takes a bit of time to slow down.

“You’ve missed the mark”, yelled the director and so we had to do it again. This took a couple of takes before we got it right.

Now the director has the button to trigger the explosives, as he is the one who decides exactly when things are to blow up. To make the explosion even more dramatic I was to fly between a V structure where propane gas was being pumped out. The idea being to explode the helicopter in this V structure to dramatically increase the explosion effect.

It was up to the director to press it at the right time, however, on the take he pressed the button far too early and the effect was lost. The director goes ballistic and after looking at the rushes, shouts at me “You bloody fool - you weren’t far enough forward.” “I’m sorry”, I said, “I was travelling forward but you are the one with the button – you didn’t have to press it that early.”

One of the director’s assistants pulled me to one side and told me that I couldn’t speak to the director like that. I replied that I wasn’t going to take the blame for what was clearly his mistake. Filming stopped while we had a sandwich and a cup of tea, after which the director came up to me and apologised. He said that he was sorry, that it was his fault and that he had accused me in the heat of the moment. “No problems”, I said and so we went to film the scene again.

We got out a new £20,000 model and I took off. This time things went perfectly and the director was right on cue. The explosion that followed was superb, it couldn’t have been any better. The noise was unbelievable. At the time I had my head out of the door of the hide as I couldn’t see properly through the safely glass. My helper should have pulled me back but didn’t because the intensity of the explosion and the rocking that followed took him by surprise. Just as I pulled my head in you could feel and hear the bits of the model hitting the Perspex window, so I guess I was pretty damn lucky.

The next morning they fished the blown up model out of the water and found it was completely destroyed. It’s interesting that I’m sad when my own models get destroyed but not this time. I had been paid to build the model, so it was theirs and not mine.

When I saw the finished film at the premier in London, it was fantastic to see what they had done with the model flying sequences. They had superimposed people sitting in the helicopter firing machine guns, none of which were in the original model. It looked so real.